Black Organizing in Pre-Civil War Illinois: Creating Community, Demanding Justice

Delegates and their Families

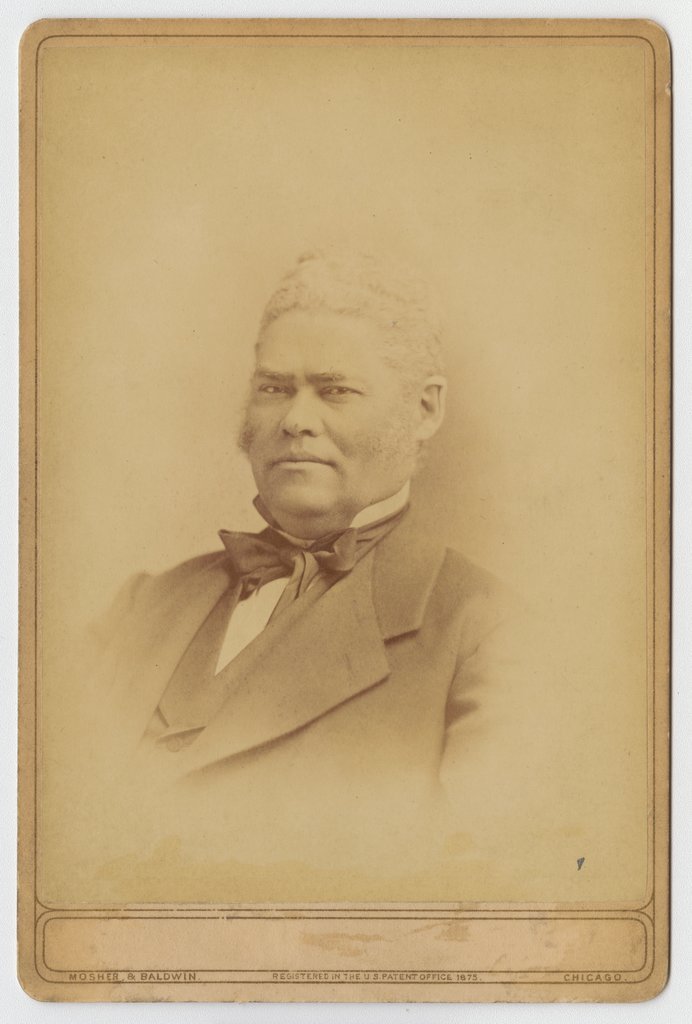

John Jones

John Jones Portrait, circa 1882

Portrait of John Jones, circa 1882. (Source: Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, ICHi-021721; Mosher & Baldwin, photographer.)

“Fellow citizens, I declare unto you, view it as you may, we are American citizens.”

— John Jones, The Black Laws of Illinois and a Few Reasons Why They Should Be Repealed, 1864.

John Jones was the most prominent Black man in mid-nineteenth-century Chicago, known for both his activism and his wealth.

Jones was born in Green County, North Carolina, on November 3, 1816. His mother was a free Black woman, and his father was a German immigrant whose surname was Bromfield. Fearing that John’s freedom was at risk, his mother apprenticed him at age nine to a man named Sheppard.1

Sheppard took Jones to Memphis, where Jones worked as an apprentice for various tailors, including Richard Clere. Jones, still a young man, became concerned that Clere’s relatives would try to claim he was a slave and assert control over his life. He returned to North Carolina to gather proof of his freedom and then, back in Tennessee, went to court to demonstrate that the terms of his apprenticeship had been broken and he was entitled to freedom. Jones won his lawsuit.2

While in Memphis, John Jones met and fell in love with Mary Jane Richardson, the daughter of a free African American blacksmith. Mary’s family soon relocated to the up-and-coming city of Alton, Illinois. John followed them, and he and Mary married in Alton in 1841. Four years later, they moved to Chicago with their infant daughter, Lavinia.3

John Jones thrived as a tailor in Chicago and quickly emerged as one of the Black community’s most energetic leaders. In 1847 delegates met in the state capital of Springfield to draft a new state constitution. Jones insisted, in letters published in the Chicago Tribune, that Black Illinoisans were entitled to full citizenship, including the right to vote for Black men.

Petition to Secure His Freedom

John Jones’ petition to secure his freedom in Tennessee in 1842. Issued by Valentine D. Barry, Judge of the 11th Circuit of the State of Tennessee, the petition states that John Jones, alias John Bromfield, was discharged from the service and custody of Richard Clere. Written and signed by William H. Mitchell, Clerk, and notarized in Tennessee in 1842. (Source: Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, ICHi-176937-A.)

Jones fought the Illinois black laws for two decades. In 1848 he traveled to the national Black convention that met in Cleveland, Ohio, where he was named vice president. It is there that he may have first encountered Frederick Douglass, who presided over the convention and later referred to Jones as an “old friend.” When Jones returned to Chicago, he joined with Henry O. Wagoner and other Black men to plan a strategy for getting the Illinois black laws repealed.4

Rather than repeal the laws, the state legislature intensified them. In spring 1853, after the legislature had adopted a newly repressive law that sought to ban Black migration into the state, Jones was among those who called for a statewide Black convention. That summer—together with Wagoner, Rev. Byrd Parker, and James D. Bonner—Jones traveled to Buffalo, New York, for a national Black convention that their protests had helped prompt.

All the while, Jones also worked to secure freedom for enslaved people, often in defiance of federal law. He and Mary offered their home as a safehouse on the Underground Railroad. In at least one instance, he purchased the freedom of a man who escaped slavery and was pursued to Chicago by his enslaver. By the end of the 1850s, the Joneses were in contact with the radical abolitionist John Brown, who was active in Kansas and Missouri and thinking about trying to provoke a vast uprising of the enslaved.5

Jones continued agitating against the Illinois black laws for years after the successful Chicago convention of October 1853. At the second statewide Black convention, held in Alton in 1856, he became president of the State Repeal Association, which focused solely on organizing for repeal.6

Yet Illinois legislators remained intransigent into the 1860s. Toward the end of 1864, with the Republicans in power, the political winds had finally shifted. That November, Jones published a pamphlet entitled The Black Laws of Illinois and a Few Reasons Why They Should Be Repealed. Black Chicagoans selected him to deliver their petition and serve as their lobbyist in Springfield. Finally the legislature acted, repealing the state’s infamous black laws on February 7, 1865.7

Painted Portrait of John Jones, circa 1865

Portrait of John Jones painted by Aaron E. Darling, circa 1865. (Source: Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, ICHi-062485; Aaron E. Darling, artist.)

Jones returned to Chicago triumphant. At a meeting to celebrate the victory, Jones harked back to the long history of slavery in North America and represented himself an embodiment the nation’s mixed African and European heritage: “Fellow-citizens of African descent, and fellow-citizens of European descent, it is an historical fact that while the Mayflower was landing her precious cargo of Europeans on Plymouth Rock, a Dutch galliot was landing her equally valuable cargo of Africans on James River, in Virginia, and the two races have now met in the person of your humble servant.”8

John Jones continued to press for racial justice. In 1865 he traveled to Springfield to lobby for legislation that would allow Black men to vote. In the winter of 1866, he was part of a delegation of Black men who met with President Andrew Johnson in the White House and tried to persuade him to support federal measures to protect African Americans’ rights and ensure that Black men had the right to vote. Johnson was not interested and rudely rejected them.9

Finally, the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, required Illinois to grant voting rights to Black men. The next year, Jones was elected Cook County Commissioner, becoming Chicago’s first Black elected official and probably in the entire state.10

Jones prospered economically and was active in Black Masonic and Odd Fellows organizations. In 1865, a visitor reported that he owned a four-story building that was “one of the finest” in Chicago. He profitably rented out the top floors and kept his clothing business — where he employed not just African Americans but about twenty white men as well — in the basement. The 1870 Census listed his occupation as “real estate agent.”11

The great fire destroyed much of Chicago in 1871, but Jones managed to rebuild his wealth. In 1875 he hosted a grand party to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of his arrival in the city. A Chicago Tribune reporter in attendance noted that his parlor was decorated with engravings of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the abolitionist John Brown, and an assortment of Republican politicians, as well as oil portraits of himself and his family.12

Upon his death in 1879, the Chicago Tribune described John Jones as a consummate self-made man. His daughter Lavinia recalled that “none of the labors of his busy life” had given him “more satisfaction than his warfare upon the Black Laws of this State.”13

Credits

Written by Kate Masur.

References

- “Obituary. Death of Ex-County Commissioner John Jones,” Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1879. Charles A. Gliozzo, “John Jones: A Study of a Black Chicagoan,” Illinois Historical Journal, 80, no. 3 (Autumn 1987), 177-78.

- “Obituary”; John Jones (John Bromfield) document, Jan. 7, 1838, Chicago History Museum, https://images.chicagohistory.org/search/?searchQuery=%20@Horizon%20Bib.%20No.:243231/, accessed Dec. 4, 2021.

- Gliozzo, “John Jones,” 178; “Obituary”; Brian Dolinar, ed., The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 43-44.

- Gliozzo, “John Jones,” 180-81; Frederick Douglass, 1892, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Documenting the American South, University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/dougl92/dougl92.html., accessed Dec. 4, 2021.

- Interview with Mary Richardson Jones in Rufus Blanchard, Discovery and Conquests of the Northwest, with the History of Chicago, 2 (Chicago: R. Blanchard and Co., 1900), 297-301; Gliozzo, “John Jones,” 183; Richard Junger, “‘God and Man Helped Those Who Helped Themselves’: John and Mary Jones and the Culture of African American Self-Sufficiency in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Chicago,” Journal of Illinois History 11, no. 2 (Summer 2008), 117-20.

- “Proceedings of the State Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Illinois, held in the city of Alton, Nov. 13th, 14th and 15th, 1856.,” Colored Conventions Project Digital Records, accessed Dec. 4, 2021, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/262.

- “Indianapolis Correspondence,” Christian Recorder, Dec. 17, 1864; “Obituary”; Gliozzo, “John Jones,” 185-88.

- “Jubilee over the Repeal of the Black Laws,” Christian Recorder, March 4, 1865; “Interesting Letter from Chicago,” Christian Recorder, Sept. 23, 1865.

- “Interesting Letter from Chicago”; Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton, 2021), 320-21.

- “Obituary.”

- “Editorial Correspondence,” Christian Recorder, Sept. 2, 1865; “Obituary”; 1870 US Census: John Jones, Ancestry.com.

- Junger, “God and Man Helped,” 128; “John Jones,” Chicago Tribune, March 12, 1875.

- Lavinia Jones Lee to Caroline McIlvaine, April 21, 1905, John Jones Papers, Chicago History Museum.