Black Organizing in Pre-Civil War Illinois: Creating Community, Demanding Justice

Black Life in Antebellum Illinois

Patterns of Black Settlement

Despite the state’s hostile policies, Black people migrated into Illinois and worked to make homes in their new surroundings. They concentrated in the southern and western regions of the state, closest to the slave states from which many had emigrated.1

Illinois Free Black Settlement in 1850 and Enslaved U.S. Population

Use the buttons in the lower-left corner to control zoom and to view the map legend and layers. Click the three dots (…) to expand or contract the view of controls.

Interactive map showing patterns of free Black settlement in Illinois in 1850, and the enslaved Black population within the United States in the same year. Data: U.S. Census, IPUMS NHGIS.

Early Black migrants often settled near the rivers that defined the state’s borders: the Wabash to the east, the Ohio to the south, and the Mississippi to the west. At first, the state’s largest concentration of African Americans was in far southeastern Gallatin County, near the salt mines of Shawneetown. Enslaved people labored in the salt mines, and until 1825, the mines’ owners were exempt from the state’s constitutional ban on slavery.2

As the state’s Black population continued to grow, many migrants arrived from nearby slave states like Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, and Virginia (including present-day West Virginia), though some came from as far away as the Carolinas.3 At first they lived primarily in the state’s southern third, sometimes called “Egypt” because of the name of its major town, Cairo, which stood at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.4

Southern Illinois became home to independent African American settlements such as Brooklyn, right across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, that became refuges for freedom-seekers from the slave states.5

Images of Black Illinois

The following cities represent places in Illinois with the highest concentrations of African American residents in the nineteenth century. Click through the tabs to see images of each city.

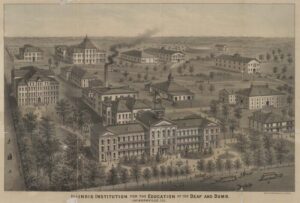

- Illustration of the Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, began in 1839. It was later renamed the Illinois School for the Deaf (ISD), and is still in operation today. Source: Courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum.

- “The 1836 Trinity Church building features a single bell tower and several archted windows and doorways. Trinity Church, an Episcopal church, began in Jacksonville in 1832.” Source: Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

- Residence of Ex Governor Richard Yates East State St. Jacksonville Ills. Source: Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

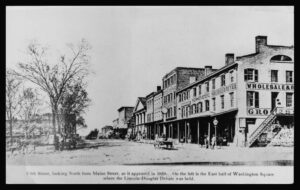

- “Fifth Street, looking North from Maine Street, as it appeared in 1858. On the left is the East half of Washington Square where the Lincoln-Douglas Debate was held. Columns on the right are part of the Court House. Signs visible on the right include Comstock & Co. Stoves, Cincinnati Store, and Wholesale & Retail Groceries.” Source: Quincy Public Library

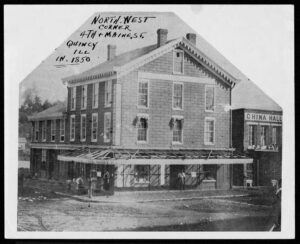

- “Tillson & Holmes Store and Post Office, northwest corner 4th & Maine Street.” Source: Quincy Public Library

- Docked boat, the St. Louis, along the Mississippi River, 1850-1864, in Quincy, Illinois. Source: Quincy Public Library

- A sketch of the view of the river in Alton, Illinois, 1836. Source: Hayner Public Library District

- “Old Alton Views – Alton,” a painting by J.M. Blair. Source: Hayner Public Library District

- “Union Baptist Church was founded in 1837 by former slaves and is one of the oldest African American churches in Illinois.” Source: Hayner Public Library District

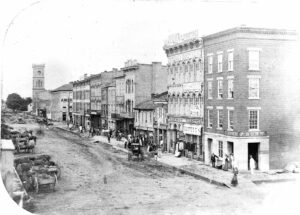

- “A photograph of the south side of the public square in Springfield taken by photographer Preston Butler,” 1858. Source: Lincoln Library

- “A photograph of the north side of the public square in Springfield taken by photographer Preston Butler,” 1858. Source: Lincoln Library

- Bird’s Eye View Map of Springfield, Illinois (1867). Source: Library of Congress

- Photographs of Randolph Street, East from Clark Street, by John Carbutt, 1865–1875. Source: J. Paul Getty Museum

- Bird’s eye view of Chicago. “This large and magnificent lithograph of Chicago in 1857 by Christian Inger is based on a drawing by I.T. Palmatary and was published by Braunhold & Sonne.” Source: Chicago History Museum

- “Chicago’s swampy setting led to its literally raising itself out of the mud. Several buildings were not only lifted but also moved to different locations. In this view of Lake Street in 1857, the work goes on in the background, while the cosmopolitan Chicagoans on horseback, in carriages, or on foot seem to pay little mind.” Source: Chicago History Museum

In the 1840s and 1850s the state’s Black population remained small, both relative to the white population and compared with the other northern border states of Indiana and Ohio. In 1850, the U.S. Census counted 5,436 Black people in Illinois, just 0.6% of the total. In comparison, the Black population of Indiana was more than twice as large, at 11,262, while in Ohio it was even larger, at 25,279. In both of those states, African Americans were about 1% of the population.6

While many Black Illinoisans were farmers living in rural areas, some gathered in cities and towns. In 1850, five towns had populations of one hundred or more African Americans: Springfield, Alton, Jacksonville, Quincy, and Chicago.

Statistics alone, however, tell us little about the lives people led and the communities they constructed with family members, friends, and neighbors. Black Illinoisans built institutions, started families, and cultivated ties to the land, laying the foundation for a movement for racial justice.

Credits

Written by Emiliano Aguilar; assistance with graphics and layout by Mikala Stokes. Edited by Kate Masur.

References

- Charles R. Foy and Michael I. Bradley, “The African American Community in Brushy Fork, Illinois, 1818-1861,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 112, no. 2 (Summer, 2019), 130.

- Foy and Bradley, “African American Community in Brushy Fork,” 131; Jacqueline Yvonne Blackmore, “African Americans and Race Relations in Gallatin County, Illinois from the Eighteenth Century to 1870” (PhD diss., Northern Illinois University, 1996), 17.

- James Gregory, America’s Great Migrations Project, accessed Aug. 24, 2021, https://depts.washington.edu/moving1/Illinois.shtml.

- Foy and Bradley, “African American Community,” 131.

- Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014), 21-56.

- J. D. B. DeBow, Statistical View of the United States, 4 (Washington: B. Tucker, 1854), 63, accessed Aug. 24, 2021, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moa/AJB5449.0001.001/63?rgn=full+text;view=image.