Black Organizing in Pre-Civil War Illinois: Creating Community, Demanding Justice

The Illinois Colored Convention of 1853

Prelude to the Convention

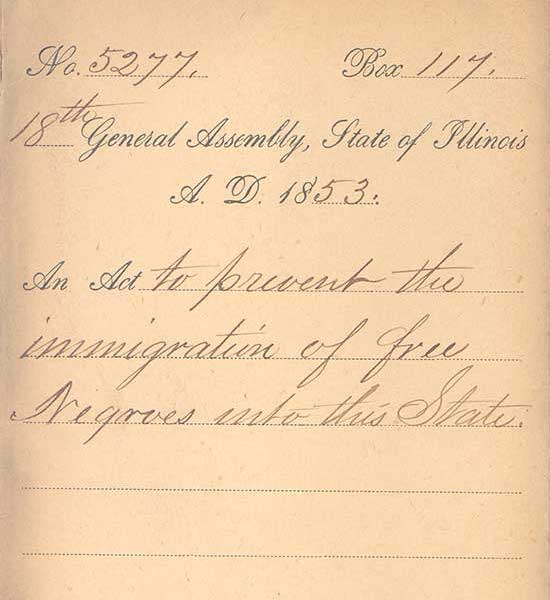

In the early 1850s, Black residents of Illinois had much to be proud of. Despite the racism they faced, they had started businesses and schools while also giving time and resources to battles against slavery and racial prejudice. Early in 1853, however, Black Illinoisans encountered a new threat. The state legislature passed a law designed to ban Black migration to the state.

The law, spearheaded by Democrat John A. Logan, stated that African Americans who entered Illinois and stayed longer than ten days could be charged with a “high misdemeanor” and, if convicted, forced to pay a hefty fine. People who were unable to pay the fine faced imprisonment and sale at public auction to a purchaser who paid the fine (and court fees) and was then entitled to the labor of the convicted person for an agreed-upon amount of time. The 1853 Illinois law was one of the harshest passed in northern states before the Civil War. Because it could result in people being forced to labor without pay, many called it the “Slave Law.”1

“An act to prevent the immigration of free Negroes into this State.”

(Source: Secretary of State, “Enrolled Acts of the General Assembly,” Record Series 103.030, Illinois State Archives.)

The “Slave Law” in Illinois drew national attention. This article, titled “Infernal Legislation,” appeared in Frederick Douglass’ Paper on April 1, 1853. (Source: Courtesy of Accessible Archives.)

The Chicago-based Western Citizen newspaper was appalled by the law, saying it was “based on injustice” and outmatched the “barbarity” of the notorious Fugitive Slave Law passed by Congress three years earlier.2

Black Chicagoans immediately protested the 1853 law. To emphasize that they belonged in the city, they held a public campaign to raise money for a new A.M.E. church building. In March, Black women hosted at least two fundraising “tea parties.” The Western Citizen told its readers that donations to the church would help Black Chicagoans fight back against marginalization and oppression.3

The existing Quinn Chapel, located on Jackson Street, was already a center of Black politics. In May 1853, Black Chicagoans held a mass meeting there to discuss the “embarrassed and distracted state of our unfortunate and down trodden fellow countrymen.” At the meeting, Henry O. Wagoner, William Johnson, and John Jones called for a statewide Black convention, the first of its kind for Illinois. R. J. Robinson traveled to the meeting from Alton and urged support for a plan, developed by the Wood River Colored Baptist Association, to raise money to support schools for Black children. Attendees agreed that a statewide convention was the best way for Black Illinoisans to “bring about a more general activity in the work of…[their] own redemption.” They elected a committee to publicize the forthcoming event.4

Chicago-based agitation against the 1853 law had national repercussions. In March, Wagoner explained in a letter to Frederick Douglass’ Paper that the Illinois Assembly had passed a “hell-black and heaven-daring enactment.” It was time, he said, for the “most active, thoughtful, prudent, and efficient [Black] men” to come together for a national meeting of African Americans.5

Interior of Corinthian Hall, 1851

An 1851 engraving of Corinthian Hall in Rochester, N.Y., where the National Colored Convention was held in July of 1853. (Source: Illustrated American supplement, by T.W. Strong. Sep. 1851, Rochester Public Library Local History Division picture file. Courtesy of Rochester Public Library, Monroe County Library System.)

This was a somber and frightening time for Black northerners. Many doubted that progress on issues of slavery and race was possible. Frederick Douglass agreed with Wagoner and called for a national convention to meet in Rochester on July 6-8, 1853. Jones, Wagoner, Rev. Byrd Parker, and James D. Bonner comprised the Illinois delegation to the Rochester convention.

At the convention, delegates were united in their commitment to fighting for free and enslaved Black people, but they disagreed about how to meet their goals. The topics of white-sponsored colonization and Black voluntary emigration proved especially contentious, foreshadowing debates at the Illinois state convention that fall. Discussions also touched on topics that resonated with the experiences of Black Illinoisans. In an “Address to the People of the United States,” leaders of the convention denounced “oppressive laws… which aim[ed] at the expatriation of free people of color.”6

Despite the vehement debate, the national convention’s statement to the American people unequivocally claimed African Americans’ status as American citizens and proclaimed their right to protection from the government of the land of their birth. Jones, Parker, Wagoner and Bonner left Rochester ready to apply all they had seen and heard to the fight for Black rights and dignity back in Illinois.

Credits

Written by Mikala Stokes and Marquis Taylor. Edited by Kate Masur.

References

- Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton, 2021), 241-242.

- “Remarks of Z. Eastman at the Fair of the African Methodist Episcopal Church,” Western Citizen, April 5, 1853.

- “The African Methodist Church,” Western Citizen, April 5, 1853; Masur, Until Justice Be Done, 245.

- “Meeting of the Colored People,” Western Citizen, May 3, 1853.

- “Letter from H.O. Wagoner,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, March 18, 1853.

- Colored national convention (1853 : Rochester, NY), “Proceedings of the Colored national convention, held in Rochester, July 6th, 7th, and 8th, 1853,” 9, Colored Conventions Project Digital Records, accessed Jan. 10, 2022, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/458.