Becoming Frederick Douglass

Women at the Colored Conventions

Attending and participating in colored conventions was very likely another way that African American women tried to experience full citizenship in antebellum America. Yet, the official record of the conventions’ proceedings (especially for those covered in this exhibit) do not provide sufficient evidence of these women contributing to the debates even as members of the general assembly. Looking carefully through archives of nineteenth-century African American newspapers and other historical materials does allow you to gain a deeper understanding about women in the colored conventions movement. Though they usually were not appointed to serve as delegates, some African American women held different roles on committees, performed as entertainers (during brief intermissions), reported on the conventions as journalists, and even ran boarding houses for those attending the conventions. Frederick Douglass casts such a broad shadow over most others involved in the colored conventions movement considering his now iconic status as an activist-intellectual. Yet, we profile the following African American women in this exhibit to bring due attention to their activism, considering how they may have influenced Douglass and perhaps many other black leaders in the struggle for abolition, equality, and social justice.

The motto on The North Star’s master head announces Frederick Douglass’ advocacy of gender and racial equality: “Right is of No Sex, Truth is of No Color, God is the Father of Us All–And All We are Brethren.”

1841 Maine State Convention of Colored Citizens held in Portland (October 6th)

- Committee on Black Life: Of those women who answered the call to attend this convention, “Miss Caroline Griffin, Mrs. A. Jackson, Mrs. Taylor, and Mrs. E. Spencer” names do appear in the official proceedings. They served along with three men on a committee that gathered statistical information about the free black populations in the region.

- Nancy (Gardner) Prince (1799-?): a native of Nantucket, Massachusetts, missionary and an abolitionist affiliated with William Lloyd Garrison. She traveled to Russia accompanying her husband, Nero Prince, but spent considerable time in Jamaica. She published a pamphlet in 1841 to inform African Americans about the difficulties of emigration to the island and to solicit aid for her missionary work there. Her travel narrative and autobiography was published later in 1850. By that time, Prince would become a leading voice in the women’s rights movement too. Only a letter written by Prince is recorded in the minutes of the 1841 convention at Portland.

Obituary for Christina Taylor Freeman.

- Activist Partners: While mostly African American men led the conventions, it was not uncommon for their wives to work alongside them in such grassroots organizing. Anna Murray Douglass was with her husband, for instance, when he first appeared in Nantucket, Massachusetts at a major gathering of mostly white abolitionists for the first time. Other women like Christiana Taylor Freeman (wife of Rev. Amos Noe Freeman) and Harriet Myers (wife of Stephen Myers) opened their homes for fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad (as did Anna Murray Douglass). Also, it is likely that since most of the conventions were opened to the public and held in churches and halls that many black women were activist partners who attended and participated in the deliberations as well.

1850 Fugitive Slave Law Convention held in Cazenovia NY (Aug 21st-22nd )

- The “Edmonson Sisters”: Mary and Emily Edmonson were once enslaved African Americans who were high profile participants at the 1850 Cazenovia convention considering its rebuttal to the Fugitive Slave Law. They performed a song and likely served on the “All-Female Committee” with white women at the convention. The Edmonson sisters became celebrities of sort given the episode of their escape and their attendance at the Cazenovia convention as it was widely covered in the national press.

1851 New York State Convention of Colored People held in Albany (July 22nd-24th)

- Mary Ann Shadd: Like other black women, Mary Ann Shadd was barred from the all-male delegations of colored conventions in the 1850s. Her campaign for emigration to Canada was in direct response to the Fugitive Slave Law, and it was controversial since it pitted her against Frederick Douglass at the time. He was in favor of African Americans remaining in the U.S. to fight for equal citizenship. Though she was rejected, Mary Ann Shadd petitioned for a delegate seat at the Colored National Convention held in Philadelphia in October 1855. She was on a speaking tour to promote emigration to Canada as a solution to the race problems in the U.S. Some male supporters, like Martin Delaney, praised and fully supported Shadd’s militancy. While the black press was dominated by mostly male editors (like Douglass), she published pamphlets to address race problems and established her own newspaper, the Provincial Freeman, as an outlet for hers and other women’s voices to be heard uncensored (Jones 113-115).

1853 National Convention of the Free People of Color held in Rochester, NY (July 6th-8th)

- Mary Jeffrey (*not profiled in this exhibit): Though Frederick Douglass advocated for Mary Jeffrey to be appointed as a delegate at this convention, even his support was not enough to convince his male cohorts to integrate the delegation. Jeffrey had a strong record of activism in New York, which included supporting Douglass’ antislavery lecture tours (Jones 103). She was an activist-partner with her husband, Jason Jeffrey, who was an abolitionist and active participate in state and national conventions.

1855 New York State Convention of Colored Men Held in Troy (September 4th-6th)

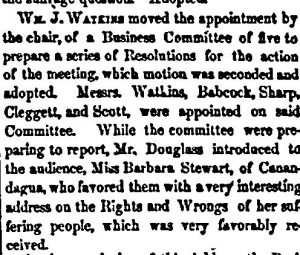

Excerpt of a report about Barbara Stewart at a “Meeting of Colored Citizens in Rochester.” Frederick Douglass’ Paper for September 21, 1855.

- Barbara Ann Steward (or Stewart): A popular lecturer on the abolitionist circuit, Barbara Ann Steward had by the “mid-1850s earned a reputation as an eloquent and persuasive speaker while touring western New York and New England” (Jones 104). Her hometown near Rochester, New York had even appointed Steward as a delegate to represent their interests at the 1853 national convention, which was supported by the Rev. Jermain Loguen and Douglass. Yet, the mostly male leadership refused to seat her as a delegate at the 1853 Rochester convention and the 1855 Troy convention as profiled in this exhibit.

“First parade of The New Woman’s Society in Possumville” [caricature of black women demonstrating for equal rights]

Date Created/Published: 1897.

Medium: wood engraving. Illus. in: Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, vol. 84 (1897 June 10), p. 375.

Black Women in the Public, Politics, and Minstrel Print Culture

Often when African American women did participate in political movements, they would be ridiculed for breaking social norms of “respectability,” or middle class decorum during the nineteenth century. Activist women were viewed as deviants who neglected their domestic responsibilities by entering the public domain of masculinity. African American women especially were targeted as public speakers in the abolitionist movement. Minstrel depictions of black people was a popular form of entertainment in American theatre by 1830s. Often, white actors in “black face” would perform as African Americans singing, dancing, and speaking in dialect as buffoons. Newspapers would also publish political cartoons with images of blacks in comical situations to mock their activism and social conditions. By the 1850s, with the splintering of women’s right from the colored conventions movement, “parodies of African American womanhood abound. They were portrayed as ‘unsexed,’ or beyond the bounds of respectability” (Jones 99). As it appears in an 1897 cartoon from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, for example, this trend would continue throughout the nineteenth century as more African American women continued to fight for racial and gender equality.