Becoming Frederick Douglass

The Presence of Power

Shadd, Mary A., 1823-1893. A Plea for Emigration, Or, Notes of Canada West: In Its Moral, Social, And Political Aspect : With Suggestions Respecting Mexico, West Indies, And Vancouver’s Island, for the Information of Colored Emigrants, 1852.

While neither Frederick Douglass nor Mary Ann Shadd were documented in the minutes of the 1851 Colored Convention, they represent leading voices on the dominant debate at the convention: whether black men and women should emigrate or remain in America. Even in their physical absence, both Shadd and Douglass’s newspapers, the Provincial Freeman and the The North Star allowed their voices and viewpoints to be heard nationwide.

Mary Ann Shadd spoke in favor of emigration to Canada. Her 1852 pamphlet, “A Plea for Emigration: Or, Notes of Canada West” encapsulates her thoughts. Douglass, on the other hand, disagreed vehemently, believing black Americans should stay and fight for their freedoms in America. He spoke numerous times on the topic. In “An Appeal to Canada,” given in Toronto on April 3, 1851, Douglass pled to Canada to help abolish slavery in America, but did not advocate for persons of color to emigrate.

In his May 7, 1851 speech “The American Slave’s Plea to Mankind,” Douglass directly disagreed with Shadd that emigrating from America was a solution to escape slavery. Douglass essentially asks mankind to help the American slave become free and remain free in America, as enslaved persons in 1851 would have been born on American soil, making them Americans.

In September 1851 in Buffalo, NY, Douglass gave “The Free Negro’s Place is in America,” which commented on how slaveholders wanted to move the free colored people out of the country. This topic was also brought up in the 1851 convention in Albany. The delegates at the convention discussed just how unjust it would be to force them all out of America.

Douglass, Frederick. “The American Slave’s Plea to Mankind.” Syracuse, NY, Frederick Douglass Papers: Digital Edition, frederickdouglass.infoset.io/islandora/object/islandora:1218#page/1/mode/1up.

Douglass, Frederick. “An Appeal to Canada.” Toronto, Canada West, 3 April 1851, Frederick Douglass Papers: Digital Edition, https://frederickdouglass.infoset.io/islandora/object/islandora%3A1212#page/1/mode/1up

Split with Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison had served as a mentor to Douglass for many years, having recruited Douglass as an abolitionist speaker soon after he escaped slavery. However, in 1851, Douglass’s views on abolition began to change, and the two men’s relationship fractured. In “Garrison Versus Douglass on the Abolition of Slavery: An Ethics of Conviction Versus an Ethic of Responsibility” Fred Guyette discusses the differences between Garrison’s and Douglass’s views on the abolition of slavery. While Garrison staunchly opposed slavery and sought its immediate abolition, his vision was non-violent. In the 1850s, Douglass began to experience a greater sense of urgency to abolish slavery, and a “greater willingness to forge connections between the rhetoric of liberation and armed intervention at the national level” (Guyette 254).

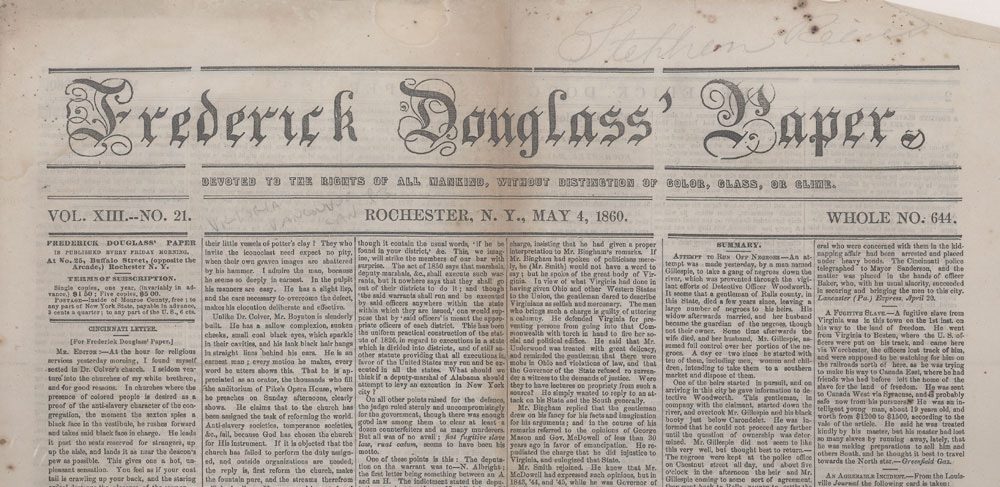

Additionally, while both men had previously opposed the Constitution as inherently racist and pro-slavery, Douglass declared that he now believed that “it ought to be wielded in behalf of emancipation” (Guyette 260). Garrison and Douglass’s increasing differences in thought created tension between the two men on the speaking circuit and in the newspaper office, causing an irreparable schism to their relationship. As a result, Douglass began to align himself with the more radical white abolitionist Gerrit Smith, whose views now more closely matched his own. Douglass and Smith merged their two independent papers, The North Star and the Liberty Party Paper, to create Frederick Douglass’ Paper.

Douglass, Frederick. “Frederick Douglass’s Paper.” Frederick Douglass’s Paper, 4 May 1860, www.bklynlibrary.org/civilwar/cwdoc017.html.

This new partnership and paper, away from Garrison’s influence, allowed Douglass to develop his voice further. The Douglass-Garrison split is key to understanding the maturation process of Douglass as an orator, writer, activist-intellectual, and abolitionist. As part of his evolving persona, Douglass declared that while he had previously used his initials, “F.D.” to identify his editorials, he would no longer do so. He began to assert that he would “assume fully the right and dignity of an Editor—a Mr. Editor if you please!” in answer to charges that a fugitive slave could not have written such editorials.

Throughout the convention movement, Douglass wields his editorial power to make his voice heard even when he is unable to be physically present, and allow his voice and that of other black activists to be heard on a national scale. Delegates at colored conventions recognize the importance and power of the black press to deliver their message more broadly. On page 40, the 1853 Rochester Convention minutes state that it is “Resolved, That in recognizing the power of the press, and the vast influence it exerts in making apparent the spirit and character of a people, we are happy in congratulating ourselves upon the fact that in Frederick Douglass Paper we possess a correct exponent of the condition of our people, as well as an able, firm, and faithful advocate of their interests, and that, consequently, we cheerfully recommend it as worthy of our hearty and untiring support.” This resolution echoes an earlier one made at the 1851 Albany Convention regarding the power of the press. Resolution 15 at this convention granted power to specific black newspapers, including Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which had been created in June of that year, to record coverage of the convention proceedings. Today, these newspapers serve as some of the most valuable archives of these historic proceedings.

Credits

Acknowledgements: “Presence of Power” page written by Kayla Schreiber, PhD student in English at the University of Southern Mississippi