Becoming Frederick Douglass

Douglass’s Connection to Stowe

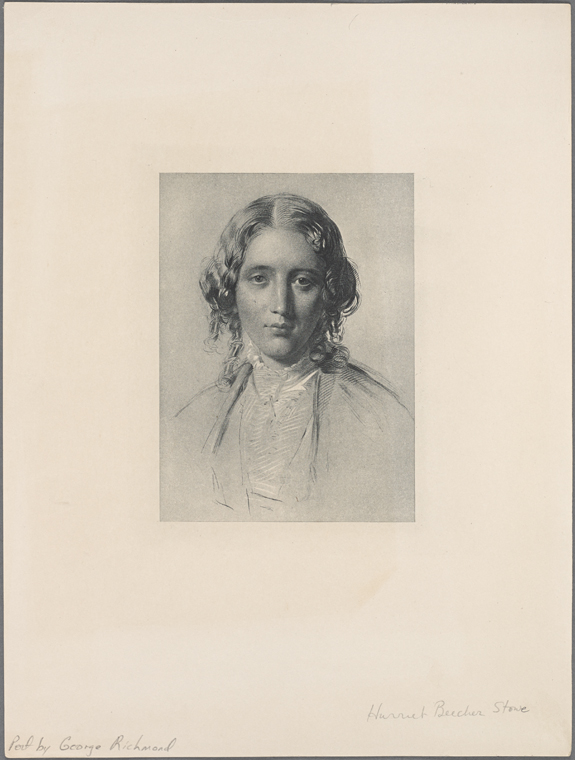

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Harriet Beecher Stowe” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1853. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/61e2f350-2542-0130-3231-58d385a7b928

In 1851 Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin and it was distributed across the country. This novel would become a major influence for the abolitionist cause and propel Stowe’s literary career into the spotlight. Uncle Tom’s Cabin would not be the only book that Stowe would write; she would go on to write over twenty books with topics intended to improve society, including A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Frederick Douglass noted the influence of Uncle Tom’s Cabin during his travels in Ithaca, New York in the Letter from the Editor section of his newspaper on July 30, 1852. He would go on to quote or make reference to Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Stowe in various speeches. One of these speeches was “A Nation in the Midst of a Nation” in early 1853, wherein he claimed that the “whole civilized world” was in the midst of reading the novel. He believed that the novel was integral in forcing a continued conversation about slavery, and not allowing it to fall by the wayside. These interactions and references mark the beginning of his interactions with Uncle Tom’s Cabin and with Harriet Beecher Stowe.

“My Dear Mrs. Stowe”: Private Talk, Public People

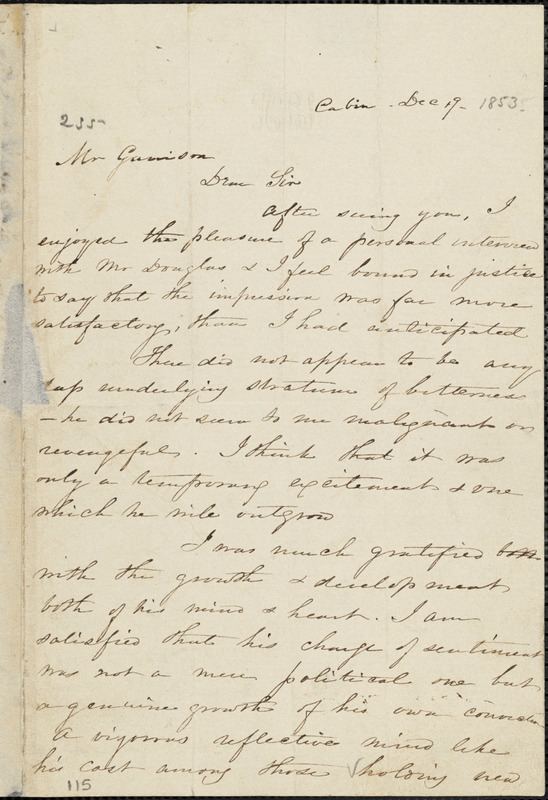

Stowe, Harriett Beecher. “Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Cabin, to William Lloyd Garrison, [1853] Dec[Ember] 19.” Received by Garrison, William Lloyd, 1805-1879, Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Cabin, to William Lloyd Garrison, [1853] Dec[Ember] 19, 19 Dec. 1853. Anti-Slavery Collection, www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:2v23xb446.

During 1853, the communication between Douglass and Stowe shows familiarity and mutual respect towards each other. Douglass took the time to read into the 1853 colored convention minutes a letter that he wrote to her in March of 1853, expressing his thanks and admiration for Stowe’s desire to do more. In this letter, Douglass requests that Stowe use her funds and influence to help establish an institute for colored people (to find out more about the Manual Labor College Initiative click here). The letter mentions how freed people are told that they need to work the land to find elevation, but that having high schools and colleges available to colored people will allow them to receive classical educations and become more than just farmers.

Following the original publication of this letter in March to Stowe the conversation has continued between multiple individuals through various newspapers. Many more nationalistic African-Americans, such as Martin Delany whom Douglass debated with over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, saw Stowe as having no way of knowing how to raise themselves up since she knew nothing, meaning she had no first-hand experience, about them or their situation. In one instance, Douglass defended Stowe against an article that was published in the Anti-Slavery Advocate. The article from the Anti-Slavery Advocate declares that is not the role or duty of the white abolitionists to assist in the efforts to educate and improve the conditions of the freed people. Douglass takes offense to this and in his response on July 22, 1853 declares “we believe that no better appropriation could be made of the funds of Mrs. Stowe, than that of establishing in this country, an institute, in which colored youth can be instructed in certain lucrative mechanical branches; and we are very happy to know that in this opinion, the excellent authoress of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fully unites.”

This friendship between Douglass and Stowe goes on to influence relationships Stowe has with other prominent members of the Colored Conventions community. In one instance, after Douglass and Garrison’s relationship fractures, Stowe sends a letter to William Lloyd Garrison defending Douglass. In this letter, Stowe contends that Garrison’s characterization of Douglass does Douglass an injustice and that Douglass’s change of views are not political, but rather views that show “a genuine growth of his own convictions.” The letter goes on to show that Stowe seems to admonish both Garrison and a Miss Weston about the unfavorable statements that they made regarding Douglass and that she must speak up against them for their remarks.

Credits

Acknowledgements: “Connection to Stowe” page written by Kathryn New (Arts and Humanities Librarian)