Working for Higher Education: Advancing Black Women’s Rights in the 1850s

Albany Enterprise Academy

To this end we have established the Albany Enterprise Academy, to be owned and controlled by colored persons, though its benefits are open to all. In thus restricting the ownership of the school to colored persons, we are actuated by no narrow prejudice, no desire to build up the wall of caste. Which we sincerely hope is crumbling to ruin, but we desire to demonstrate the capacity of colored men to originate and successfully manage such school, believing that such a demonstration will afford an argument in favor of the colored man which none can gainsay.[1]

A 1940s photograph of one of the academy’s buildings after it was turned into a residential home. James Anastas Collection, Courtesy of the Southeast Ohio History Center.

Following the closing of the Albany Manual Labor College University in 1862, Black educator and activist Thomas Jefferson Ferguson and other prominent Black Ohioans came together to establish the Albany Enterprise University. Ferguson himself attended Albany Manual Labor College at the same time as Milton Holland did. He actively encouraged persons of color to obtain training and published Negro Education: The Hope of the Race in 1866. Originally, the Albany Enterprise Academy trained teachers, but it eventually expanded its curriculum to include a wide array of subjects and training.

Apart from Ferguson, the trustees of the academy also included Peter H. Clark and Cornelius Berry. Berry’s son, Edward Cornelius Berry, attended the academy and would eventually become one of Ohio’s most successful businessmen. The younger Berry owned and operated the lucrative Berry Hotel and, like his father, supported Black education; he served as a trustee of Wilberforce College.[2]

The academy welcomed women and even built a women’s dormitory to accommodate its growing student population.[3] In 1871, thirty-three women were enrolled at the academy, outnumbering men by two. One of the academy’s graduates was Olivia Davidson who went on to become a teacher, an education activist, and public speaker. A 1921 article in The Harrisburg Telegraph mentions Davidson’s experience in Ohio: “Miss Davidson was born in Ohio, attended the public schools of the state, and was fired with an early ambition to aid her people in an educational way. She was little more than a child when she learned of the crying need for teachers among Negroes, and this crystallized her determination.”[4] Davidson taught at Tuskegee Institute and eventually married Booker T. Washington.

Another graduate was A. J. Jackson who published a poetry collection called A Vision of Life, and Other Poems. The Highland Weekly News published a piece on Jackson on 16 September 1869, lauding his literary talent: “Mr. Jackson’s opportunities for acquiring an education and cultivating the graces of literature…but Nature, as if to compensate for these disadvantages, and show that she is no respecter of color or condition, has endowed him with mental gifts of more than ordinary excellence.”[5] The article provides an excerpt of Jackson’s preface to his poetry collection and samples of the poems themselves. The academy tapped into the talents of students like Jackson, who went on to use his education to help fellow African Americans. Like Davidson, Jackson also worked as a teacher.

Support for the academy came from many sources. The Freedmen’s Bureau donated $2,000 for the construction of the dormitory.[6] While the academy received support from both Black and white patrons, the trustees made sure the academy would be solely run by African American educators. In 1885, a fire broke out at the dormitory. Black schools were frequent targets of white terrorism. With existing problems with funding exacerbated by the fire’s damages, the Albany Enterprise Academy had to close the following year. Despite this, the academy clearly made lasting marks on its students as their work and lives exemplified Black activism and excellence.

People of Albany Enterprise Academy

A former student at the Albany Enterprise Academy, Olvia Davidson is known for her activism in Black education.

Rev. Anthony Binga was a preacher and educator who served as principal of the Albany Enterprise Academy in the early 1870s.

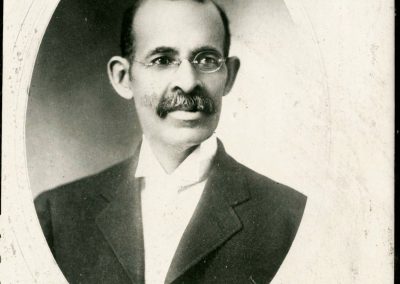

Edward Berry was a student at the Albany Enterprise Academy and was the son of one of its trustees, Cornelius Berry.

Ed C. Berry portrait, circa 1920s

Image courtesy of University Archives, Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries.

References

[1] Constitution of the Albany Enterprise Academy, 1864.

[2] “Local preservationist lament failure to save historic Berry Hotel,” Athens News, http://www.athensnews.com/news/local/local-preservationists-lament-failure-to-save-historic-berry-hotel/article_46af9642-b51d-5872-b5f3-0a21d9322f0b.html

[3] Adah Ward Randolph. “Building upon Cultural Capital: Thomas Jefferson Ferguson and the Albany Enterprise Academy in Southeast Ohio, 1863–1886.” The Journal of African American History, Spring 2002. Jstor.

[4] “Olivia Davidson, Wife of Booker T. Washington,” The Harrisburg Telegraph, 30 December 1921. Newspaper.com Distributed by ProQuest.

[5] “Poems: By a Young Colored Man.” The Highland Weekly News, 16 September 1869. Newspaper.com Distributed by ProQuest. https://www.newspapers.com/image/70791122/?terms=a%2Bvision%2Bof%2Blife%2Band%2Bother%2Bpoems

[6] Randolph, “Building upon Cultural Capital.”

Credits

Written and researched by Samantha de Vera, University of Delaware, Spring 2017.