LEWIS AND HARRIET HAYDEN

From the time they arrived as a self-emancipated couple until decades after the Civil War, Harriet and Lewis Hayden were prominent members of Boston’s African American community. The Haydens lived on 66 Phillips Street in the North Slope section of Beacon Hill–near the African Meeting House, Twelth Baptist Church (known as the Fugitives’ Church) and much of the bustling activity of Black reform.

Lewis Hayden was born into slavery in Lexington Kentucky in 1811. As a child, he witnessed the horrors of slavery first hand observing the sale of his siblings at auction and the physical violence and brutal torture enacted on slaves by masters in the south. Lewis married his first wife while enslaved. They had two sons, one of whom died shortly after birth. The sale of his wife and son by his master Henry Clay separated Lewis from his family in the 1830s. Reflecting on this event Lewis wrote, “I have one child who is buried in Kentucky and that grave is pleasant to think of. I’ve got another that is sold nobody knows where, and that I can never bear to think of.”

In 1840, Lewis married Harriet Bell who was also enslaved. Four years later the two escaped, traveling to Ohio, Canada, and Michigan before settling in Boston. The Haydens became active members in the abolitionist movement. Harriet ran a boardinghouse from their home at 66 Phillips Street (then Southac) while Lewis operated a successful clothing store on Cambridge Street. The Haydens’ home and clothing store also served as a hub for abolitionist meetings and as a stop on the Underground Railroad where they housed scores of fellow fugitives including the famous Ellen and William Craft in a public showdown with slave catchers which resulted in the Crafts winning their freedom. After the fugitive slave law was passed in 1850, the Haydens were also central figures in the famous rescues of Shadrach Minkins (1851) and Anthony Burns (1854). Lewis Hayden was elected to the state legislature in 1873 and served for one term. He worked for the Massachusetts Secretary of State until his death in 1889. Harriet passed away four years later leaving the bulk of their estate, some five thousand dollars, a large sum in that day, to support “needy and worthy colored students in the Harvard Medical School.”

Researched and written by Anna Lacy. Edited by Dr. P. Gabrielle Foreman.

Sources:

- Horton, James Oliver and Horton, Lois E. Black Bostonians; Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, Revised Edition.New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999.

- Stanley J. Robboy and Anita W. Robboy, “Lewis Hayden: From Fugitive Slave to Statesman,” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 4 (Dec. 1973), pp. 591–613. Retrieved December 3, 2013

- “Hayden, Harriet” by Shirley Yee, Black Past Remembered and Reclaimed: An Online Reference to African American History.

- “Hayden, Lewis” by Shirley Yee, Black Past Remembered and Reclaimed: An Online Reference to African American History.

- “Historic Resource Study Boston African American National Historic Site” by Kathryn Grover and Janine V. da Silva.

- An advertisement for Lewis Hayden’s clothing shop published in the December 23, 1853 issue of the Liberator.

- An article about Lewis Hayden’s funeral published in The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago) on April 12, 1889.

- A portrait of Lewis Hayden published in the New England Magazine (December 1890).

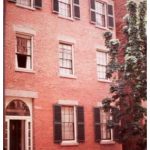

- A photograph of the Lewis and Harriet Hayden House on 66 Phillips Street in Boston, MA. The house still remains today as a site on the Black Heritage Trail. However, it is a private residence and is not open to the public.