THE FIGHT FOR BLACK MOBILITY: TRAVELING TO MID-CENTURY CONVENTIONS

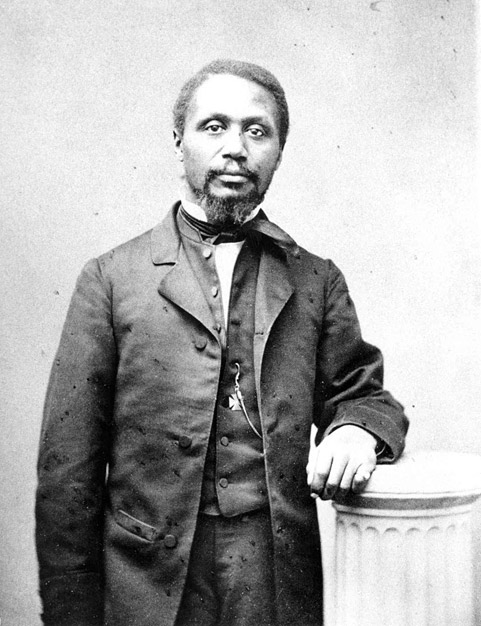

ROBERT MORRIS

“Portrait of Robert Morris,” Accessed through Smithsonian National Museum of American History; Courtesy of Social Law Library, Boston.

Robert Morris (1824-1882) was born to York and Mercy Morris, free African Americans living in Salem, Massachusetts. At age 15, Morris was employed as a servant in Ellis Gray Loring’s home where, fortuitously, Morris was called upon to serve as a stand-in for Loring’s usual mentee when he missed work; Loring was so impressed with his work that he kept him on indefinitely.1 According to William Cooper Nell, “Robert Morris Jr.,2 acquired his excellence of character and correct business habits in the office of Ellis Gray Loring, Esq., Master in Chauncery.”3 In 1847, Morris’s training under Loring paid off and he became the second African American to practice law in Massachusetts.4 In 1848, Morris’ son, Robert Morris, Jr., was born to Morris’s wife, Catharine H. Mason (whom he married two years before); on Robert Morris Jr.s’ birth records, Morris was listed for the first time as an “Attorney at Law” living in Hathorne, just outside of Boston.5 Robert Morris Jr. would later follow his father’s example and become a (less-known) lawyer. Morris continued to practice law in a number of offices throughout Boston until his death, due to heart disease, in 1882.6

Robert Morris’ participation in the 1855 Colored Convention is anything but surprising given his legal activities in Boston during the years leading up to and following the convention. Most notably, Morris worked on cases centering on African American education and the Fugitive Slave Law. In 1850, for instance, Morris took part in Sarah Roberts v. The City of Boston alongside famed lawyers and abolitionists like Charles Sumner.7 Although the Roberts family and their legal team, including Morris, did not win, their case set an important precedent for later civil rights activities including Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education.8 Morris also took part in another notable court case—his own. In United States v. Robert Morris, Morris was charged9 with aiding a fugitive slave, Shadrach Minkins, escape to Canada.10 With the help of notable abolitionist lawyers, Charles Sumner, John P. Hale (NH), and Richard H. Dana, Jr. (MA), Morris won his case.11 Five years after the 1855 Colored Convention, newspaper evidence shows a continuation of Morris’s actions against the Fugitive Slave Law and unequal treatment of African Americans in the U.S. legal system. He is noted as taking part in political activities with the hopes of “[b]lotting out “white” from statue book,”12 while also inspiring legislative action that would include African Americans into the military to serve in the American Civil War.13 Finally, in 1866 Morris ran for mayor.14 Although he was not elected to office, his campaign definitively marked his status in Boston society and politics.15 During these years he also had offices in Scollay’s Square, a major abolitionist hot spot in central Boston;16 these offices are not a coincidence considering Morris’ intensely abolitionist circle of friends. Moreover, comments like the following indicate the strength of Morris’ own abolitionism: to his protégé, Edwin Garrison Walker, Morris said, “Don’t ever try to run from our people. Do you wear gloves? If you do, take them off and go down among our people.”17

Little documentation remains regarding Robert Morris’ active participation in the 1855 Convention. He would have likely taken part (probably via informal conversations) in discussions surrounding the Fugitive Slave Law, but most especially the segregation of education. Because Roberts v. The City of Boston took part just a few years before the 1855 Colored Convention, it was probably still a subject at the forefront of Morris’ mind. Given his immense popularity during his life (a newspaper in Chicago referred to him as “Boston’s Lawyer”18), it is unfortunate that only a few critical works focus solely on Morris (one being an Op-Ed article from the New York Times19). Most articles about the Sarah Roberts v. The City of Boston case at least mention Morris’ participation, but the vast majority tend to focus on white abolitionist participants like Charles Sumner. J. Clay Smith’s text, Emancipation, focuses almost an entire chapter, “The Genesis of the Black Lawyer,” on Morris’s legal and political life.

Credits

Submitted on 22 March 2013 by Elizabeth A. Boyle, graduate student at the University of Delaware. Researched for English 634, Spring 2013, taught by Professor P. Gabrielle Foreman.

Edited by Harry Lewis and Samantha de Vera, ENGL641, Spring 2016. Taught by P. Gabrielle Foreman, University of Delaware.

References

- J. Clay Smith Jr., “New England: The Genesis of the Black Lawyer,” Emancipation (Pennsylvania: U of Pennsylvania P, 1999), 96.

- For an unknown reason, Robert Morris and his friends referred to Morris as both “Jr.” and “Sr. Given the dates of this source, this quotation is referring to Robert Morris Sr.

- William Cooper Nell, “George B. Vashon,” North Star, 28 Jan 1848, 1(4): 2, 6, 7. In William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, Ed. Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constantine Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Class P, 2002), 172.

- “Slavery: Fugitive Slave Law,” Long Road to Justice, Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed 12 Mar 2013.

- “Massachusetts, Births, 1841-1915,” FamilySearch, accessed 13 Mar 2013.

- Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, accessed 12 Mar 2013.

Interestingly, Morris and his son died within two weeks of one another in December 1882. While I could not find any correlation between these two deaths, they are noted in both obituaries and the 1883 Boston directory, which is the only source other than census and death records to identify Catharine Morris as still living in the family’s 78 West Newton home. Morris was eulogized by his protégé, Edwin (sometimes Edward) G. Walker.

- Sarah Roberts v. The City of Boston evolved out of the Roberts family’s struggles to enroll Sarah in a local elementary school. Despite living just blocks away from her nearest elementary school, Sarah was forced to walk past five of these schools because they were designated for white children (See “Roberts vs. City of Boston Begins.”) After facing such discrimination, Sarah’s father, Benjamin F. Roberts, sued the city with the hope of gaining Sarah entry into one of these local establishments (see “Sarah Roberts” page for more information).

- “Black Entrepreneurs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Brochure,” New England Economic Adventure, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, accessed 12 Mar 2013.

- Smith, Emancipation, 117n39.

Morris was charged alongside James Scott, Lewis Hayden, Elizut Wright, and Joseph K. Hayes.

- “Slavery: The Ordeal of Shadrach Minkins.” Long Road to Justice, Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed 12 Mar 2013.

- Smith, Emancipation, 117n40.

- “Letter From Boston,” The Weekly Anglo-American, 14 April 1860, pg 1.

- He also helped in the recruitment of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the first official African American unit in the U.S. Army (Wilson).

- Smith, Emancipation, 99.

- In the years that closely followed this election, Morris and his family are documented as moving from their home on 100 Washington Avenue to a new one on 78 West Newton. Morris is also reported to have converted to Catholicism at some point towards the end of his life. Unfortunately, written comments surrounding the circumstances of his conversion are unavailable.

- Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, accessed 12 Mar 2013.

- Stephen Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walker: The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America (Boston: Beacon P, 2003), 50.

- “Boston’s Lawyer Dead,” The Conservator, 23 Dec 1882, pg 1.

- Stephen Kantrowitz, “Equality First, Guns Afterward,” Opinionator, The New York Times, published 1 Mar 2013, accessed 20 Mar 2013.