THE COLORED CONVENTIONS AND THE CARCERAL STATES

BLACK WOMEN REFORMERS

This section explores African American women reformers’ role in continuing the Colored Conventions’ protest against incarceration. The Colored Conventions influenced future Black activists, ensuring that the movement would live on in other forms. The turn of the century signaled a change in attitudes as well, and Black women took the chance to be at the helm of reform movements.

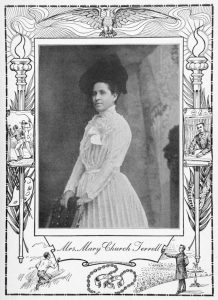

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Mrs. Mary Church Terrell” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1902.

She worked with Frederick Douglass, whose participation in Colored Conventions are well noted. While studying at Oberlin College and working at Wilberforce, Terrell would have been acquainted with Colored Conventions attendees and delegates. She was also part of Washington, DC’s Black elite, and her social circle was never bereft of relentless Black activists. In 1907, Terrell published an essay in the magazine The Nineteenth Century titled “Peonage in the United States: The Convict Lease System and the Chain Gang.” In her essay, Terrell adroitly showed that the chain gang system in the South was a continuation of slavery. Damningly, she also revealed how the courts and lawmakers rendered the Constitution meaningless by supporting such system. Terrell’s essay is a powerful testament to not only her intelligence, but also to African American women’s fierce resistance against racial injustice.

White House Conference Group of the National Women’s Council; (Mary McLeod Bethune, center; Mary Church Terrell, to her right), 1938.

In old age, Terrell fought against racial oppression as fiercely as she did when she graduated from Oberlin College. Above is a picture of Terrell with the members of the National Women’s Council. At age 86, she sued a restaurant in Washington, DC for denying her and her companions service because of their race. The case reached the US Supreme Court, and Terrell won. Below is copy of Terrell’s essay:

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Mrs. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Prominent Woman of Boston, Leader of the Club Movement Among Colored Women” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900.

Born to a prominent Black family in Boston, Massachusetts, Josephine St. Pierre (1842–1924) grew up to be an staunch activist. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin benefitted directly from the activism of Sarah Parker Remond and Charles Remond’s father, John Remond. Segregation in Boston prevented Josephine from acquiring quality schooling, so her parents sent her to Salem, where John Remond had fought to desegregate schools.

She was one of the founding members of American Woman Suffrage Association, the lead organizer of National Federation of Afro-American Women, and a charter member of the NAACP. She also founded the Woman’s Era Club and served as the editor of Woman’s Era, the first national newspaper of its kind—established and ran by African American women for African American women. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was instrumental in shifting the National Association of Colored Women’s focus from racial uplift to prison reform.

Josephine St. Pierre married George Lewis Ruffin, the first African American to graduate from Harvard Law School and the first Black judge in the US. While married to Josephine St. Pierre, George L. Ruffin attended at least three Colored Conventions. The couple worked closely together, so it is highly likely that Josephine not only knew the discussions in the conventions but she could have also attended some. After her husband’s death, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin unrelentingly continued her work and raised her daughter Florida Ruffin to become an activist and writer, much like her parents.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and her daughter both edited Woman’s Era. Ruffin had hoped to revise Woman’s Era and “devote itself especially to advocating the cause of Prison Reform in the South.” [2] In her speeches, Ruffin chastised fellow white club women for devaluing Black children and ignoring the abuses wrought upon Black women.

References

1. “Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin.” Retrieved from http://masshumanities.org/programs/shwlp/honorees/#ruffin

2. William H. Alexander, Cassandra L. Newby-Alexander, Charles H. Ford. Voices from within the Veil: African Americans and the Experience of Democracy. (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 301.

Photograph courtesy of Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Butler is known as an education activist. She was the founder and first president of the National Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers Association. Like many Black club women, Butler was very much invested in racial uplift and the “strategy of respectability.” [1] Through education and Christian influence, Butler believed that clubwomen could help improve the lives of working girls. However, as Sarah Haley noted, Butler and the others “suspended [their strategy of respectability] in opposition to black women’s incarceration on the convict lease, knowing that poor black women required concerted defense rather than defense commingled with training or judgment or reform.” [2] Mobilizing alongside Terrell, St. Pierre Ruffin, and others, Butler publicly decried the convict lease system. In 1897, two years after Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin convened the National Association of Colored Women, Selena Sloan Butler submitted a paper to be read at the NACW’s meeting in Nashville, Tennessee. The Chain-Gang System is a vivid and powerful condemnation of Georgia’s incarceration system. Growing up in Thomasville, Georgia, the young Selena would have witnessed laboring Black prisoners on her hometown’s roads. It is, therefore, no surprise that her activism extended beyond education. Her protest against the convict lease system indicates that Butler saw the incompatibility of racial uplift discourse in this fight.

References

1. Sarah Haley. No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow. (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 253. 2. Ibid.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Ida B. Wells” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1893.

The most outspoken and prolific critic of lynchings and incarceration, Ida B. Wells [Barnett] often inverted the logic of racism, revealing the barbarity of a system ruled by whites and emphasizing the humanity of African Americans. Wells’ crusade against lynching encompassed a ferocious protest against Black incarceration. In 1893, she published a collection of essays titled, The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. In Chapter III: “The Convict Lease System,” Wells exposed the economic motivations behind the lease system, the treatment Black men and women were subjected to, as well as the court system’s forefront role in destroying Black lives. As Wells noted, the justice system constantly turned a blind eye from white criminals but targeted African Americans, giving the latter egregious punishments for trumped up crimes. As discussed in the exhibit, the vilification of Black womanhood and glorification of white womanhood had very real consequences. Wells was certainly aware of this. As such, she ended her essay with a factual statement that speaks of the brutality of these consequences: “This made the second colored female hanged in that [South Carolina] within one month. Although tried, and in rare cases convicted for murder and other crimes, no white girl in this country ever met the same fate.”[1] References: [1] Ida B. Wells. The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. Urbana Champagne: University of Illinois, 28.