HARPER 200

RECONSTRUCTION

The period of Reconstruction in the United States refers to the era immediately following the Civil War, typically dated from 1865 to 1877. During this complex and tumultuous era, Congress aimed at reintegrating the Southern states that had seceded and addressing the status of formerly enslaved people. White terrorism ran rampant as former Confederates violently thwarted efforts to uplift African Americans. Still, many Black activists in the North ventured down to the South to help Black southerners by building schools, teaching, lecturing, and providing other forms of service and humanitarian aid. Beginning in 1867, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper spent time in South Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia, lecturing for the African Methodist Church. As Melba Joyce Boyd notes, the theme of her lectures was “Literacy, Land, and Liberation,” alluding to the importance of education and land-ownership in attaining self-determination and liberation.[1]

At the same time, Harper continued writing and publishing and gave some of her most important speeches. In May 1866, Harper delivered her speech “We Are All Bound up Together” at the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York. Moreover, her anthology, Sketches of Southern Life, published in 1872, offered a poignant portrayal of African American life in the post-Civil War South. Centering around the characters of formerly enslaved persons, Aunt Chloe and Uncle Jacob, Sketches explores the complex transition from slavery to freedom, the importance of education, and race relations during Reconstruction. Harper employs vernacular speech to represent her characters’ voices, blending poetry with social commentary and historical documentation. The collection addresses the challenges and hopes of Black southerners, showcasing their resilience and strength while providing valuable insights into the social and political climate of the era.

Like many African Americans, Harper tragically trusted the Freedmen’s Savings Bank, an institution chartered by the US Congress to help Black southerners build wealth. However, mismanagement and corruption spelled the demise of the bank in 1874, ruining the financial prospects and hopes of thousands of African Americans. Harper herself had planned that her savings would benefit Mary in the future as she entrusted them to her. The records of the Freedmen’s Bank offer insights into Harper’s movements during Reconstruction as well as little known facts about her life. Explore the tabs below to read these records.

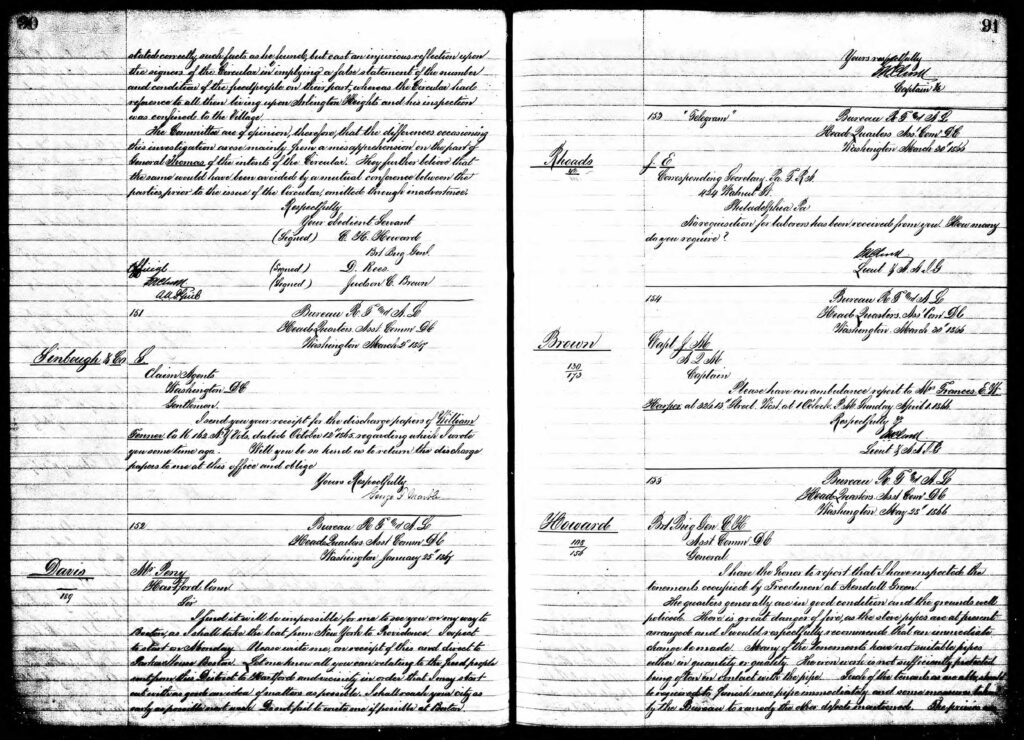

Harper appears in some correspondences of Freedmen’s Bureau agents. In a correspondence dated March 30, 1866, a lieutenant orders a captain to have an ambulance report to Harper, indicating that she was involved in providing humanitarian aid to refugees from slavery who fled to Washington, DC. The nation’s capital experienced an influx of refugees after during the war. When President Abraham Lincoln, compensated DC enslavers upon emancipating their enslaved servants, more refugees sought refuge in the city. The federal government was wholly unprepared to deal with the humanitarian crisis that followed.

Source: “Records of the Field Offices For the District of Columbia, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1870.” NARA Series M1902, Roll 1. Record Group 105, Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1861-1880. National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

In June 1867, Harper opened an account with the Freedmen’s Bank. On her account record, she wrote her daughter’s middle name as Ann rather than Ellen and indicated that she was a widow.

Source: Department of the Treasury. “Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874.” Record Group 101: Records of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-2006. ARC Identifier: 566522. Roll 08: Savannah, Georgia; Jan 10, 1866-Dec 17, 1870. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

The 1871 record of Harper’s account names her daughter as the beneficiary of her savings: “In case of death of depositor, she desires that her deposits be sent to the Baltimore Brch [Branch] for her child.” Like many African Americans, Harper trusted the bank only to have her hopes dashed when it collapsed. The federal government took no accountability and did not compensate the bank’s clients who lost their life savings. Investigation into the bank’s collapse dragged on through the years. After which, political leaders still did nothing to address the economic injustice inflicted upon thousands of Black families.

Source: Department of the Treasury. “Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874.” Record Group 101, Records of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-2006. ARC Identifier: 566522. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

In another record from late 1871, Harper indicated her mother’s name, Sydney Watkins but left her father’s name blank. This record is so far one of the very few documentation noting her mother’s name.

Source: Department of the Treasury. “Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874.” Record Group 101, Records of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-2006. ARC Identifier: 566522. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

REFERENCES

[1] Melba Joyce Boyd, Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E.W. Harper, 1825-1911 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994), 120.

CREDITS

Written by Samantha de Vera